Keynesianism is a movement in economic theory that emerged in response to the challenges of the Great Depression (the economic crisis of 1929-1939). The trend is named after the English economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes is considered one of the founders of macroeconomics as an independent discipline. The main work of the scientist is The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

The Great Depression gave rise to the division of economic theory into microeconomics and macroeconomics. Although macroeconomic topics such as economic cycles and the theory of money had been studied before, the merit of the English economist John Maynard Keynes is that he systematized this knowledge and laid the foundation for a new direction of research, which for a long time differed from the rest of economic science not only thematically, but also methodologically.

Since the 1980s, however, the methodological distinction between micro- and macroeconomics has been erased. Now all macroeconomic science, including modern Keynesianism, is based on clear microeconomic reasoning, i.e. on the behavior of individual individuals and firms. Macroeconomics differs from microeconomics only thematically – it studies processes relevant to the economy as a whole: economic growth, fluctuations in economic activity, inflation, the behavior of exchange rates.

Prominent Keynesian scholars include the last two Federal Reserve governors, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen. Keynesians Olivier Blanchard and Kenneth Rogoff were recently chief economists at the International Monetary Fund, and Stanley Fischer was previously chief economist, later heading the Central Bank of Israel. The author of famous economics textbooks, Gregory Manchu, is also a Keynesian supporter.

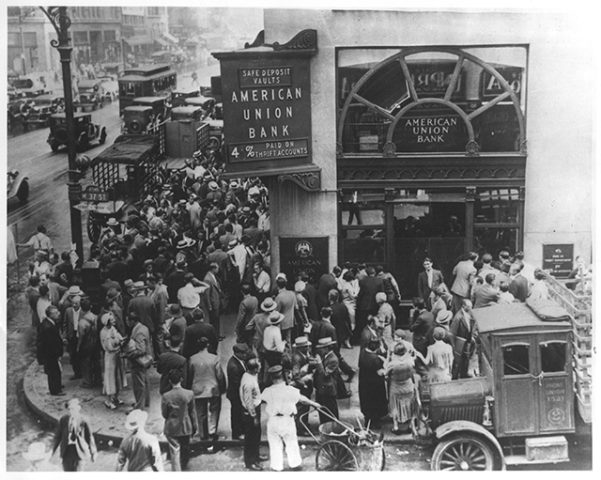

The Great Depression and the Emergence of Keynesianism

Keynes proposed a fall in aggregate demand as an explanation for the Great Depression, the causes of which he vaguely labeled “the animal instincts of investors.” That is, the panic that began in 1929 after the stock market crash culminated in the fact that firms stopped spending money on investment spending.

Aggregate demand is the desire on the part of all economic players to purchase the goods and services that the economy produces. It can be the desire on the part of consumers, that is, people who purchase goods and services for their own needs. It can be the desire on the part of firms to purchase investment goods or to build new facilities for their production. During recessions most often we see a drop in investment demand: firms abandon projects, they don’t hire people to build a new factory or a new building, and this causes unemployment. Also, aggregate demand includes purchases from the government, which makes a government order, and from the outside sector (exports).

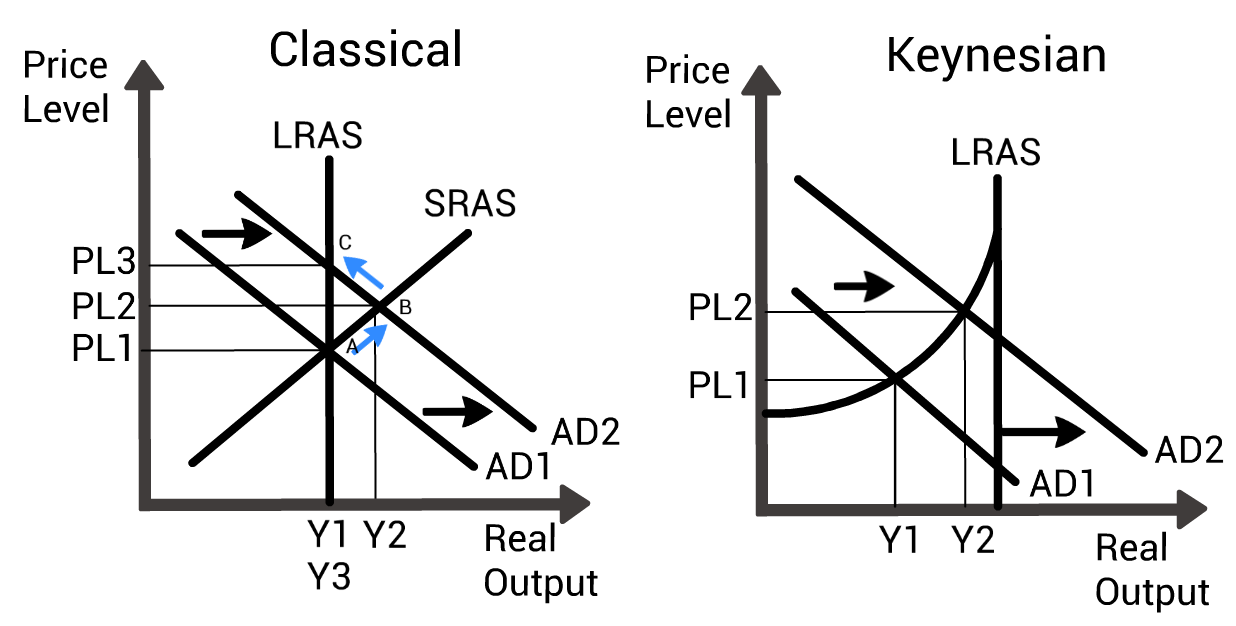

When the Great Depression began, the logic of classical theory was that a reduction in aggregate demand should have caused prices and wages to fall. But Keynes made another important observation, that prices and wages did not adjust in time to the new equilibrium and firms could not lower them. And at the old prices they could no longer sell as many goods as they had sold before. So firms were forced to cut production and lay off some workers. The laid-off workers lost income, demand shrank even more, and this led to a cyclical fall in the economy over a long period of time.

Shrinking money supply

A couple of decades after Keynes’ work, an alternative view of the causes of the Great Depression emerged. It came from economists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz. They believed that the fall was caused not so much by “the animal instincts of investors,” but by a contraction in the money supply allowed by central banks in various countries, most notably the United States and France. This contraction spread to other countries through the then-existing gold standard system.

This view has become dominant over time. But by and large it does not contradict Keynesian theory, because a fall in the money supply is also a fall in aggregate demand. Falling money supply means that credit has become less available. Firms and households did not get credit, did not spend the money on what they had planned to spend it on before the recession began.

Positive Keynesianism

In economic science and in public discourse, Keynesianism means different things. Here it is important to distinguish between positive and normative Keynesianism.

Positive Keynesianism is an economic theory that tries to explain observable phenomena. First of all, it tries to explain what is called the economic cycle, that is, to find the reasons why the economy periodically goes through periods of recession (recession).

Both early Keynesian theory and the modern, new Keynesian version assume that such recessions are nonequilibrium phenomena, that is, some deviations from normality associated with imperfections in the market economy. The imperfection most often highlighted is price rigidity, that is, the inability of prices to adjust quickly to changing conditions. The second important part of positive Keynesianism is the hypothesis that such downturns are in most cases (though not all) due to falling aggregate demand.

Normative Keynesianism

Normative Keynesianism answers the question of what to do in the event of an economic downturn. And Keynesianism is often understood in public discussion as any ideology of government intervention in the economy. I think this point gets more attention than it deserves because an economist who believes in a Keynesian explanation of recessions does not necessarily support large-scale government intervention at all.

Government regulation of the economy

Keynes, when formulating his theory in the 1930s, was in favor of fairly active intervention in the form of government spending, more regulation of the market. This ideology dominated the postwar period, in the 1950s and 60s, so it is understandable where this attitude toward the Keynesian viewpoint came from in the public discussion.

In the 1970s a wave of economic deregulation began in the world. Some think it was excessive, and others, on the contrary, that it was overdue. Most economists who consider themselves Keynesians in the positive sense, that is, who believe in the Keynesian explanation of recessions, do not call at all for a return to the kind of regulation we saw before the 1970s.

The only industry where more regulation has been called for again since the 2008-2009 crisis is the financial sector. Many would argue, however, that this crisis was caused in large part by misguided actions by governments that gave implicit guarantees to big banks in the years before the crisis. These guarantees allowed the banks to behave excessively risky, knowing that in a crisis they would be bailed out at taxpayer expense.

There is no consensus among Keynesian scholars here. For example, Nobel laureates Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz are greater proponents of government intervention in the economy than many other Keynesians. And there is Gregory Manchu, for example, a Harvard professor and economic adviser to U.S. President George W. Bush, a Keynesian in his academic beliefs and one of the authors of the new Keynesian theory. Nevertheless, Manchu takes a rather conservative view, believing that it is better for the state to intervene as little as possible, and if it does intervene, then only through monetary policy. This is not regulation, but the provision of credit to the economy in times of recession.

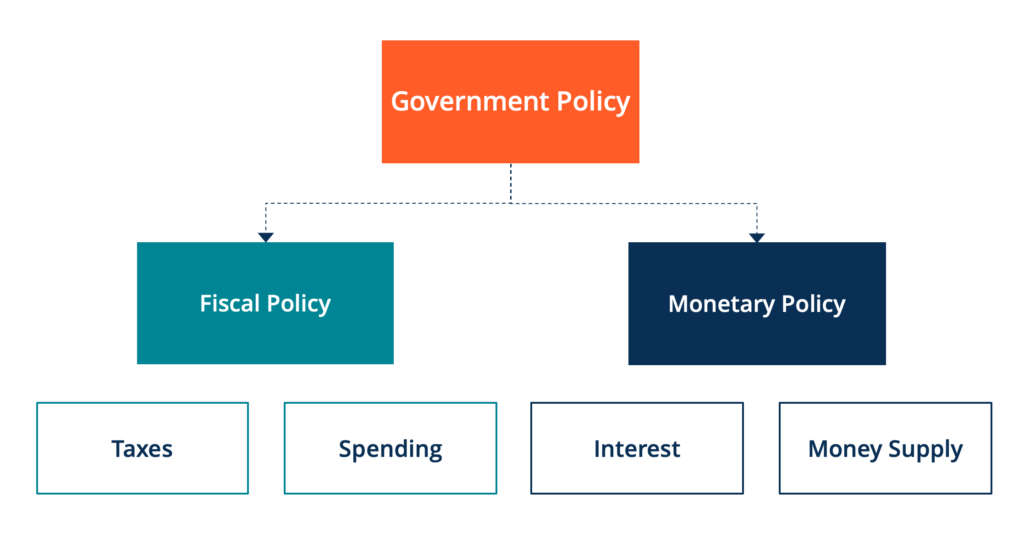

Fiscal Policy

If aggregate demand falls and a recession begins, the natural reaction to this problem is to try to stimulate it artificially. The government has two tools here: fiscal policy and monetary policy.

Fiscal policy, which Keynes argued for, implies that the government has to present demand when the private sector is not presenting it. The government increases public spending on public needs: it begins to build roads and bridges.

Not everyone agrees that this is reasonable, because the budget policy is not operational, it is often voluntaristic, immediately there are a lot of issues related to corruption and inefficient use of budget funds. When we run, especially on an emergency basis, large amounts of money through the government, inevitably there will be inefficient spending. But during the Great Depression, this was the policy that became dominant.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy is now used to a greater extent, especially if the recessions are not such great cataclysms as the Great Depression. As part of monetary policy, the central bank lowers the interest rate at which it lends money to the economy. Thus it adds money to the economy, and the economy, receiving cheap credit, increases consumer and investment spending. Thus aggregate demand is restored to its original level.

Monetary policy is now considered more effective: it is more expeditious and less voluntaristic than fiscal policy. Although, as the crisis of 2008 showed, during major cataclysms governments use both of these tools.

Monetarism

In public discourse, Keynesianism is often contrasted with monetarism as an ideology of, respectively, non-intervention by the state.

Monetarism is a paradigm introduced by the American economist Milton Friedman. He believed that the economy is inherently stable and does not need to be artificially stabilized by either fiscal policy or active monetary policy. All the government has to do is to make sure that the money supply grows smoothly at a constant rate.

Excessive growth in the money supply leads to inflation, which is bad for the economy. And if the money supply suddenly falls, as it did in the early 1930s, it can lead to economic collapses up to and including the Great Depression. That is, Friedman believed that the Great Depression was the fault of the authorities, who stimulated a fall in the economy by allowing the money supply to fall. This view, that all the government should do is oversee a smooth growth of the money supply, was originally presented as monetarism.

But in that form, monetarism no longer exists. In terms of theory, monetarism has long been conflated with Keynesianism, because monetary policy is one way to stimulate the economy during a recession, that is, to stabilize around a long-term trend. And unexpected fluctuations in the money supply, caused either by mistakes of the authorities or by some perturbations in the financial market, are aggregate demand shocks, which Keynesians, among others, discuss.

Keynesianism and the financial crisis

Aggregate demand can fall for a variety of reasons. For example, one of the main causes of the 2008 global financial crisis was the bursting of the housing market bubble in many countries: real estate became very cheap, and people who felt rich stopped feeling rich, so they began to spend less on buying goods and services. At the same time, a large number of banks went bankrupt, so they stopped lending to firms and households alike. As a result, both firms and households, having lost access to credit, stopped spending money either on the purchase of goods and services or on investment spending.

The reaction to such crises through artificial stimulation of demand is an absolutely standard policy, and 2008 was no exception. The vast majority of countries involved in this task both monetary policy (the most striking manifestation was the series of quantitative easing in the US and Europe) and fiscal policy.

Neo-Keynesianism

The traditional version of Keynesianism that existed until the 1980s was later replaced by Neo-Keynesianism. The main ideas in the new version remained the same: the dominance of the aggregate demand side in explaining recessions and the explanation of these recessions as deviations from market equilibrium primarily due to the slow adjustment of prices. The differences are for the most part methodological and therefore more understandable to academic economists.

New Keynesian theory is based on microeconomic justifications. Serious attention is paid to how specific individuals and firms behave in the models, how their expectations are formed, and how decisions are made. Keynes neglected this not because he considered it unimportant, but because it was impossible to encompass everything at once. But the neglect of these aspects led to the fact that some formulas turned out to be wrong, which was the reason for the policy mistakes that were made in various countries in the 1970s. This resulted in very high inflation everywhere.

Some economists after those events felt that Keynesian theory with the idea of disequilibrium fluctuations and rigid prices was wrong in itself, and so they founded another theory called the new classical theory. Other economists, however, decided that some of the mistakes that had been made were not a reason to tear down the whole theory, but rather to fix it, to rewrite it with more attention to the microeconomic rationale. This has been done, and, by and large, the basic conclusions of New Keynesianism remain the same as they were 50-60 years ago.

The New Classical Theory

The New Classical theory proceeds from the idea that the economy is always close to equilibrium and that economic fluctuations are equilibrium phenomena. In practice, however, few people still believe that the Great Depression or the 2008 crisis were equilibrium phenomena and that unemployment during these episodes was voluntary. So I take the new classical theory as a methodological framework, more interesting to scholars than to practitioners. Not surprisingly, it is the Keynesians who dominate among prominent practicing economists working in central banks or finance ministries.

At the same time, the new classical theory is the basis for modern Keynesian theory. That is, Keynesians take the new classical theory and add to it some market imperfections, such as the slow speed of price adjustment. Within these models, it turns out that if we believe that prices come to equilibrium quickly, then we live in a neoclassical world. If we think prices take a long time to adjust, then we live in a Keynesian paradigm.

Classical and Keynesian theory in their modern form easily coexist at the same conferences, in the same journals, and often in the mind of the same economist. And sometimes it makes sense to use one tool to answer one question and sometimes another tool, depending on which question we are studying. That is, these are not isolated theories.